Not too long ago, we stumbled across a discussion about the need for large-gauge car audio speaker wire to be connected to a high-power amplifier. The comments on the post were prime examples of how little some audio enthusiasts understand about the signals going to the speakers in their car audio system. So, to help as many people as possible understand the subject, we put together this article to explain why you don’t need 12-AWG wire for your tweeters.

Audio Signals – Amplitude and Frequency

The amount of voltage produced by your amplifier is dependent on the volume setting and the frequency content of the audio signal. Suppose you’re listening to a recording of an electric guitar. In that case, your amplifier will produce significantly less power than it would take to reproduce the lowest notes of a synthesizer or bass, even at the same perceived volume level.

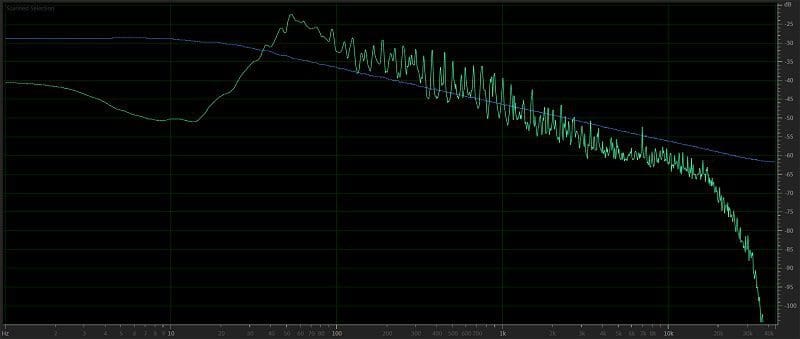

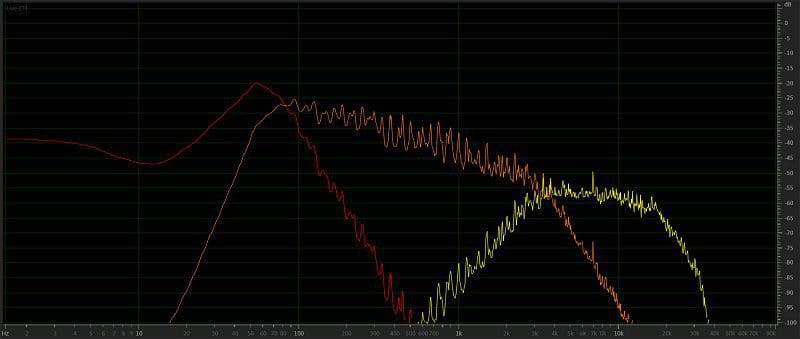

Why do higher frequencies need less power to reproduce? Most of the sounds we hear follow the same approximate shape as pink noise. If you analyze the energy in a pink noise waveform, you’ll see that its amplitude attenuates at a rate of -3 dB per octave or -10 dB per decade as frequency increases.

If you have a typical car audio system, then you may have a subwoofer or two to handle reproducing audio frequencies below 80 Hz, midrange drivers to handle the sounds from 80 to 3,500 Hz and tweeters for those frequencies above 3,500 Hz. The graph below shows the energy fed to the subwoofers, midrange drivers and tweeters using these crossover points.

It’s clear to see that the tweeters are receiving a lot less energy than the midrange drivers in the doors. In fact, it’s about 20 dB less at the highest level. If you had 100 watts going to the door speakers, your tweeters would only need 1 watt of power to keep up. In this example, the average amplitude of the signal going to the mids compared to the tweeters is 13.9 dB louder. So, you need about 4.1 watts for those tweeters if the mids are getting 100 watts. With nearly 5 dB more output required, the subwoofers would need 316 watts, assuming they had the same efficiency as the midrange speakers.

Power in Alternating Current Signals

A commenter in that thread wrote, “Yeah, but it’s AC, not DC,” as if to imply that an AC signal wouldn’t deliver as much current to the speaker. For pure sine waves, this with where the Root Mean Square (RMS) value comes in. An AC sine wave of, say, 10 volts RMS can do the same amount of work as 10 volts DC.

Music isn’t a single constant sinusoidal waveform. It varies in amplitude and frequency. As such, we need to look at an average level. To keep our example simple, let’s use 300 watts, 100 watts and 4 watts for the math involved in calculating how much power is lost due to the resistance of speaker cabling. We’ll also maintain the simplicity of the example by assuming all the speakers in the system have a nominal impedance of 4 ohms.

Current in Car Audio Speaker Wire

For our example, our 300-, 100- and 4-watt power levels translate to 8.66, 5 and 1 amp of current flowing through the respective speakers. Let’s use a piece of 12-AWG speaker wire with a length of 10 feet for our benchmark. If the speaker wire is full AWG spec and is made from pure copper, the 10-foot length will have a total resistance of about 36.3 milliohms. The voltage drop in the wire will be 0.314, 0.181 and 0.026 volts which, if my math is correct, represents a reduction in output of 0.157, 0.091 and 0.018 dB, respectively. In short, these differences aren’t going to be audible at anything other than when the volume is turned up all the way. At even one notch down, those reductions diminish significantly. With the dynamic characteristics of music, it’s safe to assume the average required power is 1/10 of the maximum.

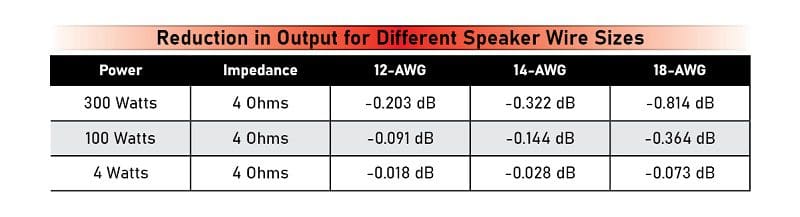

What happens if we run 14- or 18-AWG wire instead of 12-AWG? The chart below shows the reduction in output at the most extreme cases with test tones being played. For your tweeters, it just doesn’t matter. For the mids, at full power, maybe there is a minute loss that might affect the balance of the system. Should you use 18-AWG speaker wire with your subwoofer? Probably not.

What happens at normal listening levels? Say you are commuting to work and the radio is on so you can hear traffic and news with the odd song thrown into the mix. With the typical midrange driver having an efficiency of 86-88 dB at 1W/1M, you are likely to be averaging a lot less than 1 watt of power to the doors. For argument’s sake, let’s say you are. To maintain the same relative output levels, the sub would be getting 3 watts and the tweeters are at 40 milliwatts. Our losses in the speaker wire drop to imperceptible levels of 0.063 dB on the woofers, 0.036 dB on the mids and 0.003 dB on the tweeters. Still worried about speaker wire size?

Let’s Look at More Subwoofer Math

Car audio companies seem to like to design car audio subwoofer amplifiers that produce their maximum power into low impedances. We’ve already looked at the sacrifices in amplifier efficiency and increases in distortion at low impedances in another article.

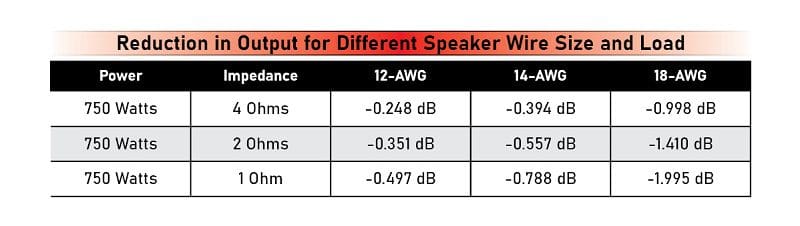

In short, for the same power delivery to the subwoofers, lower load impedances require more current to flow through a speaker’s voice coil. More current means more energy is wasted in the speaker wire due to its resistance. Let’s cook up another example – 750 watts into 4-, 2- and 1-ohm loads with 12-, 14- and 18-AWG speaker wire. Here are the results:

As you can see, this is yet another good reason to avoid amplifiers that require low load impedances to produce large amounts of power. OK, 750 watts through an 18-AWG conductor that’s 10 feet long is a pretty extreme example, but it punctuates the point pretty clearly.

In reality, you will never deliver full power to all the speakers in your car, save for maybe the subwoofer if you compete in SPL contents. In those cases, where tenths or maybe even hundredths of a decibel matter, having oversized speaker wire and amplifier power cable is impossible. Knock yourself out and have your installer run eight-AWG power cables to the subs! For the rest of us who listen to music at even modestly reasonable power levels, 14-AWG speaker wire is well more than adequate, and your tweeters don’t need anything over 18-AWG. Drop by your local specialty mobile enhancement retailer to find out about the audio upgrades that are available for your car or truck. Spend the money you’ll save on not buying monstrous speaker wire for your tweeters and midrange drivers on better speakers.